Taking leave of our senses

Our work and personal lives are increasingly being played out in the digital world. Journalist Chris Muyres mourns the loss this has on enjoying things through our senses. In Issue 36 he tells us about refinding his senses.

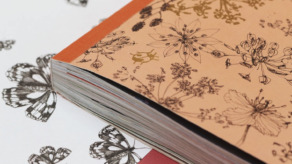

One sunny day in the fall of last year, I took the train to Freiburg, a city on the edge of the Black Forest in Germany. While walking down Salzstraße, I was drawn to the Buchhandlung zum Wetzstein bookstore with its 1950s display window made of wood and brass set in a sandstone façade. I could smell the books through the display window (even though this is of course impossible, your brain can trick you every now and then).

Scent, sight, sound, touch

I decided to walk into the store purely to be able to take a whiff of that printed paper aroma that, for some reason, always makes me happy. Once inside, I saw copper chandeliers hanging from the ceiling, wooden bookshelves and glass cases leaning against the walls, displaying handwritten letters and first editions. Soft carpet covered the floors, muffling every sound and giving the store an added intimate ambiance.

My eyes searched the shelves, finally coming to rest at a broad, bound spine: Der Zauberberg (The Magic Mountain) by Thomas Mann. I just had to buy the book, ignoring the voice in my head telling me that there was no way I was going to read all 984 pages in German.

The voice was wrong; I have since finished the book. I say this with more sadness than pride, because closing a compelling novel for the last time always puts me in a melancholy mood. For weeks, the book never left my side; it was on the table next to the couch, my nightstand, the breakfast table.

The pleasure of sensitivity

It was always where I could see it. It was a pleasure, over and over, to feel the book’s linen cover in my hands, to run my fingers over the embossed drawing of the mountain sanitarium. And finally, to lift the satin bookmark and open the masterpiece to the page where I had left off.

In reading Der Zauberberg, I clearly realized that turning a page evokes a different emotion than the act of swiping on a device. After all, swiping is a gesture of contempt that you literally cannot feel in your fingertips. Our ‘feelers’ can flawlessly register the difference between rough, smooth, thick, thin, supple and stiff surfaces.

The rise of touchscreens is sadly causing the pleasure we get from this sensitivity to disappear. However, statistics show that the sales of e-books are slowly declining and those of real books are rising. This phenomenon runs parallel to an increase in the number of bookstores that are opening their doors instead of closing them, as observed by the American Booksellers Association.

- Read more from Chris about refinding his senses in Issue 36.

- Find Der Zauberberg here.

Text Chris Muyres Photography João Silas/Unsplash.com